The Rise of Psychedelic Therapies in Treating the Mental Health Crisis

The Rise of Psychedelic Therapies in Treating the Mental Health Crisis[1]

The social, economic and political fallout from COVID-19 has the potential to exacerbate the global mental health crisis, which could increase cases of suicide and depression over the coming quarters. Historically, mental health practitioners have prescribed antidepressants to help afflicted patients, but the long-term efficacy of these drugs is questionable and varies widely based on the severity of the patients’ depression[2]. However, a resurgence in the field of psychedelic research for mental health has shown promising early signs for treating a wide variety of mental health disorders and this leads to many questions: What exactly are psychedelic drugs? Where is the research today, and what are the dangers associated with these drugs? We explore these topics and more in the blog below.

The Mental Health Crisis

Media outlets and public health experts have emphasized the importance of physical distancing & hygiene to slow the spread of COVID-19 and “flatten the curve”, some of which we highlighted in our previous post COVID-19 & Cannabis. However, less focus has been given to the negative trickle-down effects of COVID-19, as the health, economic, and social impacts of the virus have led to an increased prevalence of isolation, anxiety, fear, depression and substance abuse. These impacts have exacerbated the mental health crisis already plaguing millions.

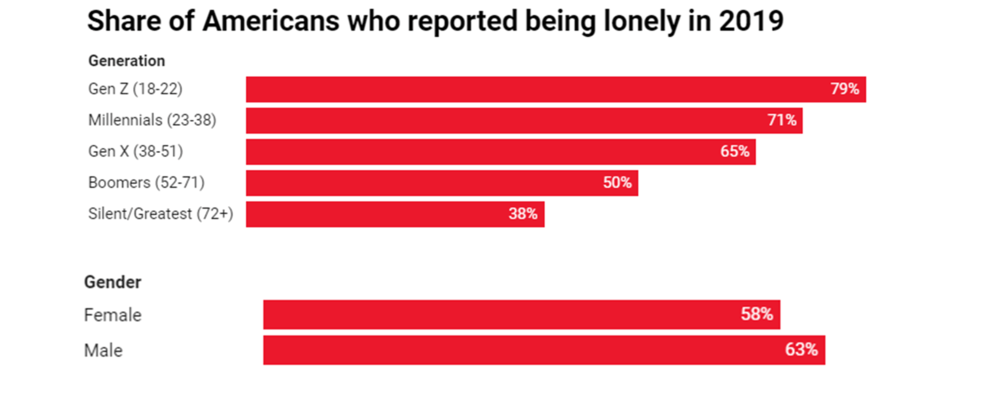

Even before COVID-19, millions of Americans suffered from mental health ailments, including 40mn afflicted with anxiety, 20mn with substance abuse disorders and 17mn with major depression. A January report from health-insurer Cigna indicated that around 61% of American adults felt some degree of loneliness, with younger adults disproportionately afflicted with these feelings.

Source: Nemecek, Douglas M.D. “Loneliness and the Workplace: 2020 U.S. Report”. Cigna. January 2020. Accessed May 9, 2020: https://www.cigna.com/static/www-cigna-com/docs/about-us/newsroom/studies-and-reports/combatting-loneliness/cigna-2020-loneliness-report.pdf.

Existing Mental Health Treatments

Since 1959, only 29 active substances have been approved by the FDA to treat mental illness. There has been limited innovation in the mental healthcare sector since the introduction of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (“SSRIs”), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (“SNRIs”), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (“MAOIs”), and tricyclic antidepressants (“TCAs”), collectively known as “antidepressants”.

While antidepressants do slightly outperform placebos in treating depression, their efficacy appears to diminish over time. Further, approximately one-third of people with depression do not respond to treatment[3]. This may be driven in large part by the fact that antidepressants treat the symptoms of depression, but do nothing to help the patient confront the underlying trauma that caused the depression in the first-place. Additionally, common antidepressants such as Zoloft & Prozac have significant side effects and delayed onset of action. Many patients discontinue treatment due to the side effects, which may include headaches, anxiety, decreased sex drive, diarrhea, sleep problems and nausea.

The History of Psychedelics

Over the last c. fifteen years, research into psychedelic treatments for mental health disorders has seen a major resurgence, led by medical institutions including N.Y.U., Johns Hopkins, U.C.L.A. and Imperial College in London. Scientists are eager to reconsider the therapeutic potential of these drugs on mental health. But what exactly are psychedelics? The term was coined by psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond in 1957 and means “mind manifesting”, to refer to the fact that these compounds help the mind manifest its deepest qualities. Common psychedelics include LSD (aka “acid”), psilocybin (the hallucinogenic component of “magic mushrooms”), peyote (“mescaline”) and ketamine.

Between 1953 and 1973, the federal government spent four million dollars to fund 116 studies of LSD, involving more than seventeen hundred subjects[4], understated figures as they exclude classified research activities. The results of this early research were so promising that it drove psychiatrist Dr. Stanislav Graf to state, “What the telescope was for astronomy and the microscope for biology, psychedelics will be for the understanding of the human mind.”

“What the telescope was for astronomy and the microscope for biology, psychedelics will be for the understanding of the human mind.”

So, what happened? The counterculture movement, with Harvard Professor Timothy Leary as the most notorious bad actor, began excessively and irresponsibly taking psychedelics, leading to a collision with the Nixon Administration and the “War on Drugs”. Leary had started conducting experiments with psilocybin and LSD at Harvard from 1960 to 1963, but became impatient with the scientific research process and started disseminating psychedelics broadly. This led Richard Nixon to at one point declare him, “the most dangerous man in America”. The backlash against psychedelics led to their inclusion as Schedule 1 substances in the Controlled Substances Act (“CSA”) of 1970. This scheduling effectively halted any additional research into psychedelic treatments in the field of psychiatry for almost forty years.

The Resurgence of Research & “Breakthrough” Therapy Designation

The resurgence of psychedelic research received a kick start in 2006, when researchers at Johns Hopkins completed a study on psilocybin that showed the drug produced a range of acute perceptual changes. At two months, the volunteers rated the experience as having substantial personal meaning and spiritual significance, and attributed to the experience sustained positive changes in attitudes and behaviors[5].

Since the 2006 study, much of the research into psychedelics has focused on their impact on the brain’s default-mode network. The default-mode network was discovered in 2001 by neuroscientist Marcus Rackle at Washington University and is where the brain goes when it is not busy. The default-mode network is effectively the regulator of the brain and is involved in metacognitive functions including self-reflection, rumination, thinking about the future & the past, etc. In other words, the default-mode network can be considered the seat of the self or the ego[6].

Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris of Imperial College London describes the default-mode network variously as the brain’s “orchestra conductor”, “corporate executive”, or “capital city,” charged with managing and “holding the entire system together.” Carhart-Harris believes that the psychedelic experience can help people by relaxing the grip of the ego and the rigid, habitual thinking it enforces. Carhart-Harris believes that people suffering from other mental disorders characterized by excessively rigid patterns of thinking, such as addiction and obsessive-compulsive disorder, could benefit from psychedelics, which, “disrupt stereotyped patterns of thought and behavior.” In his view, all these disorders are similar ailments of the ego.

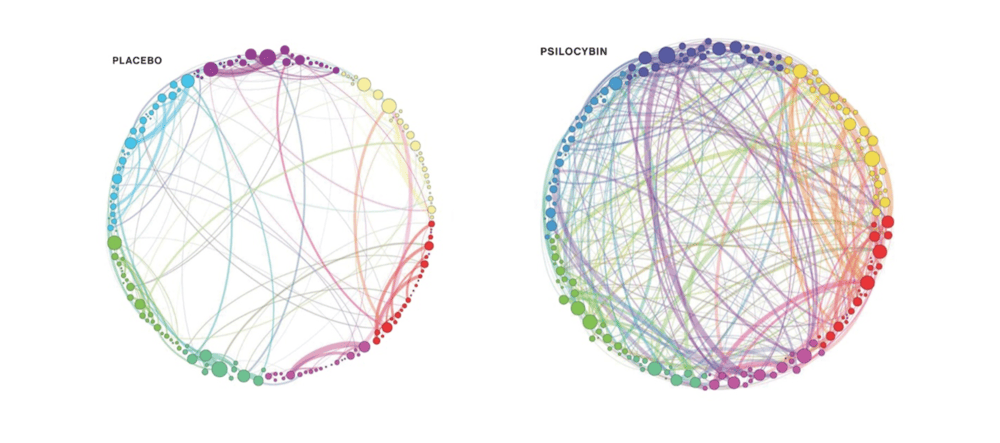

Dr. Carhart-Harris’s lab mapped the neurological connections of volunteers on placebos as well as psilocybin. They found that while the psilocybin led to a precipitous reduction in activity in the default-mode network, it enabled a vast array of different networks in the brain that do not usually talk to one another to connect. A visualization of the brain connections with and without psilocybin is presented below:

Source: Pollan, Michael. How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us about Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. London: Penguin Books, 2019.

A helpful analogy as to how psychedelics can help to change your mind is to imagine your brain as skiing on a ski mountain. Over time, your brain repeats behaviors that effectively create worn ruts that continue to get more deeply ingrained over time. But when taking psychedelics, your brain snows five feet of fresh powder, where you’re now given the flexibility to create a new track in your behaviors.

Where are we Today?

The legal application of psychedelic treatments may occur faster than many would expect. As of May 2020, Compass Pathways, a company backed by renowned Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel, is currently running FDA Phase 2B clinical trials on the usage of psilocybin therapy for treatment in depression[7]. The FDA granted the program “breakthrough therapy” designation – a process designed to expedite the development and review of drugs that are intended to treat a serious condition and in which preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the therapy may demonstrate substantial improvement over available therapy. Additionally, in March 2019, the FDA approved the use of Johnson & Johnson’s Spravato, a nasal spray derived from ketamine, for treatment-resistant depression.

Eleven labs are running clinical trials to test the theory that MDMA[8] (aka “ecstasy” or “molly”) can help treat post-traumatic stress disorder. The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (“MAPS”) is already running a Phase 3 trial on MDMA for treating PTSD and could receive FDA approval as early as 2021. This treatment also received a breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA. Further, Usona Institute’s psilocybin program received breakthrough therapy designation for the treatment of major depressive disorder, and Johns Hopkins is opening a new $17mn center for psychedelic research. The promising early results from these organizations and others are likely to drive even more companies to dive into the field of psychedelic research and test their efficacy on additional mental health disorders.

The Dangers of Psychedelics

While it’s our view that drug prohibition inevitably makes the prohibited substances significantly more dangerous – a topic on which we just scratched the surface in our post The Iron Law of Prohibition – those dangers remain significant and real. The first offense for possession of an illegal Schedule 1 substance can carry a penalty of up to one year in jail, a $5k fine, and suspension of your driver’s license for six months. Further, as these drugs must be purchased on the black market, there is no quality control or effective dosage system. This means the substances could be laced with other unknown, harmful drugs. Regarding dosage, LSD in clinical settings is typically administered between a tiny 25 and 150 micrograms. This is such a small dosage that overconsumption of the drug can occur easily when taken illegally.

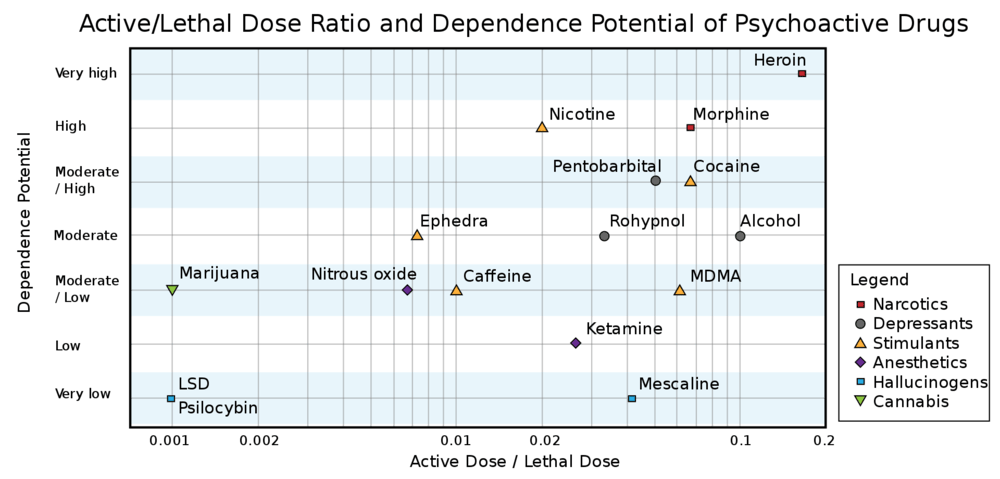

Additionally, psychedelics have significant risks even when legally taken in pure form. On the positive side, there is no know lethal dose of psilocybin or LSD – they’re not toxic and they don’t stay in your body for very long. There’s also no evidence of the drugs causing physical addiction. See below a chart representing common drugs with regards to their potential for lethality and dependence:

Source: Gable, R. S. (2006). Acute toxicity of drugs versus regulatory status. In J. M. Fish (Ed.), Drugs and Society: U.S. Public Policy, pp.149-162, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

However, it’s important to note that the promising early results for potential psychedelic treatments are all being done in a clinical setting, with trained clinicians supporting patients during their experience. Taking these drugs with a positive mindset and in the appropriate setting has been shown to be a critical component for a positive experience. Having an “unguided” trip outside of a clinical setting can be incredibly dangerous, as psychedelics are disruptive to your usual defenses. People without their usual defenses can do careless things on psychedelics like walk into traffic or step off of a building.

Additionally, people on psychedelics are left in a vulnerable, easily manipulated state, which can leave them susceptible to abuse if taking the drugs in the company of nefarious characters. Because of these concerns, we view it as unlikely that there will ever be an “adult-use” market for psychedelics like there is for cannabis, but rather that their usage will be restricted to clinical settings. While these psychedelic therapies show early promise for treating mental health disorders, they remain illegal in all fifty states and the associated dangers are significant. As such, they should not be used illegally or without professional medical supervision.

[1] KEY Investment Partners remains focused on investing in the legal US cannabis market. We expect the legal psychedelic therapeutics industry to evolve over the coming decade, and have written this post as a short primer as we develop our internal thesis on the psychedelics sector.

[2] Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, et al. Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010; 303(1):47-53. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20051569/.

[3] Oaklander, Mandy. “New Hope for Depression”. Time Magazine. July 27, 2017. Accessed May 18, 2020: https://time.com/4876098/new-hope-for-depression/.

[4] Pollan, Michael. “The Trip Treatment”. The New Yorker. February 9, 2015. Accessed online May 18, 2020: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2015/02/09/trip-treatment.

[5] Griffiths RR, Richards WA, McCann U, et al. (2006) Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology 187: 268–283. Accessed online May 19, 2020: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/press_releases/2006/griffithspsilocybin.pdf.

[6] Ferriss, Tim. Interview with Michael Pollan (Episode 313). The Tim Ferriss Show. Podcast audio. June 26, 2018. https://tim.blog/2018/05/06/michael-pollan-how-to-change-your-mind/.

[7] Piore, Adam. Shroom-Therapy Startup Edges Toward FDA Approval. January 6, 2020. Bloomberg. Accessed May 19, 2020: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-01-07/psychedelic-mushroom-therapy-startup-edges-toward-fda-approval.

[8] MDMA is not technically a psychedelic drug, but rather a stimulant with psychoactive effects.

DISCLAIMERS: This site is not intended to provide any investment, financial, legal, regulatory, accounting, tax or similar advice, and nothing on this site should be construed as a recommendation by Key Investment Partners LLC, its affiliates, or any third party, to acquire or dispose of any investment or security, or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction. An investment in any strategy involves a high degree of risk and there is always the possibility of loss, including the loss of principal. Nothing in this site may be considered as an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell securities or other services.